|

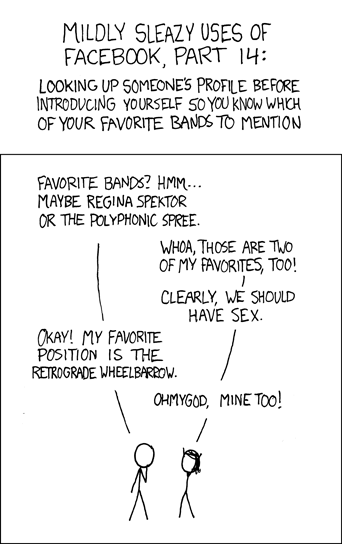

Historically, new forms of media (such as film and television) have often been initially perceived as threatening or dangerous, evidenced by the “moral panics” perpetuated in popular media. These moral panics typically portray new media as granting children access to an “adult world” that escapes the protective gaze of the family. Online social networking sites have been criticized for enabling sexual transgressions, promoting popularity contests, and encouraging members to publicize personal information. For these very reasons, these sites have become increasingly popular vehicles for creating virtual private spaces within which young people negotiate the everyday concerns that dominate their personal lives. Nevertheless, the popularity of these sites is frequently disparaged by users themselves in the form of a deeply embedded dystopian cynicism, as many of my informants perceive the medium as a poor replacement for face-to-face interaction, encouraging voyeuristic and narcissistic practices that they see as symptomatic of our increasingly digital generation. Everyday conversations concerning online social networks frequently elicit a good deal of anxiety. One source of anxiety is uncertainty regarding who has access to the information that is found on these sites. Unintended audiences include parents, educators, law enforcement agencies, potential employers, corporations, and government intelligence agencies. Another source of anxiety has to do with members’ personal relationships with this new medium. In my interviews people have touched upon various issues triggered by engagement with these sites, longstanding student concerns that are often intensified online, such as quick judgments of others, procrastination from schoolwork, social anxiety, lowered self-esteem, casual or obsessive “stalking,” and outright addiction. Like all forms of communication media, online social networks are heavily influenced by legal and economic factors that shape the manner in which individuals engage with them. At the same time, modern communication media have also rendered these forces increasingly visible to the public. The content of online social networking sites is primarily provided by the members themselves, and in order to retain popularity the sites must maintain their trust and favor. The most controversial issue with regard to the Internet is privacy, and most sites that provide services must also develop a Privacy Policy that balances user interests and compliance with the law. The relationship between online social networks and legal authorities is a frequent source of tension. Facebook’s privacy policy explicitly states:

Compliance with the law is practically universal in the privacy policies of online social networks, including MySpace and Tribe. Many of my friends perceive me as the local expert on all things relating to social media, and regularly ask me how much and for what purposes the information they provide to these services is tracked by government agencies. In response, I point out that since the inception of the Patriot Act in 2001, Americans have been stripped of a great number of civil liberties in the war against terrorism. In today’s political climate, it would seem that freedom of speech is secondary to the higher priority of defense against potential acts of political violence. In 2005, for example, a University of Oklahoma student was visited by the Secret Service in response to references he made on Facebook regarding the assassination of President Bush (Epstein 2006). Having heard countless stories of government control and censorship of electronic information, many people express some degree of mistrust and fear. A fellow student relates her struggle between this somewhat abstract fear and the comforting knowledge that one is merely a face in the crowd:

Dana belongs to a subset of savvy users who are conscientious about the content they make publicly available on their Profiles. However, she went on to acknowledge that despite her precautions, key words of her Profile might nevertheless be used to target advertisements. While the top-down gazes of the government and the companies themselves provide the common incentive for self-censorship and distrust, commercial advertisers are seen as directly targeting consumers in a manner that is viewed as an aesthetic annoyance and a reminder of the capitalist culture that has tended to exploit all forms of popular entertainment. Popular online social networking sites are truly, in the words of a fellow student, “a marketer’s wet dream.” This corporate presence is especially prominent on MySpace, and generates one of the most common criticisms of the site. Most users, however, have developed high tolerance for advertisements. Internet-savvy youth often proclaim they don’t even notice advertisements or scams; rather, their eyes scan and filter out meaningless content, the cursor scrolls past in pursuit of the message. The better a person articulates her tastes online, the likelier it is that advertisements will be of greater pertinence. As a general rule, for instance, Google maintains an extensive, dynamic archive of user data, which serves as the backbone for its popular advertisement program, AdSense. Thus, their advertisements are geared toward the individual user based on the type of websites she visits and the subjects she displays interest in according to the specific search terms queried. In fall of 2007, Facebook and 41 affiliated companies (such as Blockbuster) initiated Project Beacon, which tracks user interactions through the companies’ sites, aggregates them with Facebook data, and publishes this information on a member’s News Feed (see Appendix B). Most Facebook users were unaware of the Project, which initially took advantage of them through an “opt-in” strategy, making participation the passive default. This move was met with widespread alarm and condemnation in the blogosphere, prompting Facebook to eventually post a public apology and grant users the capacity to control what is displayed to their Friends:

Nevertheless, Beacon continues to collect data on what people do on these affiliate sites, which is then sent to Facebook along with identifying IP addresses (Perez, 2007). Not even those who have deactivated their accounts are immune. “It’s scary,” Robert says, “Facebook is becoming evil.” Nevertheless, the utility of Facebook for negotiating everyday social practices generally take precedence over the egregious invasions of privacy that most users suspect occur. The trend is not abandoning Facebook- it's far too useful. However, the site's reputation is definitely tainted, and some Facebookers are using the site to form or join Groups that promote awareness of Facebook's privacy policies and petition for change (such as “Petition: Facebook, stop invading my privacy!” with over 75,000 members). Tracking consumer data is nothing new, but online social networks enable corporate access to increasingly personal information. The vast majority of negative consequences of publicly displaying one’s personal information arise when “inappropriate” information is made viewable to more local levels of authority, such as employers and school faculty. Uploaded images and references to illicit activities and offensive ideas (such as homophobic speech) have been subject to investigation by high schools and colleges alike, and have sometimes resulted in suspension or even expulsion of the offending student. In my brother’s senior year at high school, several students were called into the principal’s office to discuss inappropriate photographs of underage drinking posted on public MySpace Profiles. The principal had created an account and was therefore able to enter into a domain that these underage students had considered to be their own. His infiltration into their “private sphere” was met with widespread indignation. “I would have told them to fuck off if they brought me in,” my brother informed me, “it’s private shit.” As a result of the incursion, he and his friends realized the necessity of making their Profiles private. Across the country, similar cases were covered in the popular media. As MySpace and Facebook have risen in popularity, more recent media coverage has exposed the threat of employer investigation into the Internet identities of potential employees. Colleges and universities advise students on the importance of “cleaning up” one’s virtual identity. Maria, who is a Resident Advisor, told an interesting story about her training:

Controversy regarding Facebook’s privacy policy was tinged with resigned acceptance that the policy, in the words of an informant, “is very strange, and not a privacy policy, really.” Some members allude to this imagined disapproving audience in the crafting of their Profiles, as exhibited by the following Profile picture of a Wesleyan senior:

This is but one of countless examples of the ways in which online social networkers are responding to the growing threat of surveillance. Many choose to implement privacy features that allow them to maintain intimate, closed social networks within which they portray themselves as they truly see themselves. As a result, it's become increasingly common for me to be unable to access the Profiles of people I'm not Friends with. Others have simply taken to deleting much of their Profiles, leaving just an e-mail address, a witty or ironic comment, and maybe a funny picture. Most first-generation Facebookers express some degree of distrust/disgust for the site, often a great deal of it. Regardless of how they talk about them, however, young people continue to use the site regularly for everyday social practices- it's a way to easily invite people to parties and share photos from said parties, to visually organize one's social network and keep track of geographically distant friends, alumni, and old high school buddies, and to find out the sexuality or relationship status of that boy you've been admiring from afar. If a college student is not on Facebook, she’s going to be somewhat out of the campus loop. The same factor applies, albeit to a lesser degree, to MySpace and Tribe. For many, it's become as habitual to check one’s favored social network site as it is to check e-mail. Nevertheless, self-censorship is a necessary response to the increasingly blurred boundaries between one’s public and private spheres online. Computer-mediated communication is like speech in that it allows for casual, convenient, and immediate interactions. Additionally, it shares several aspects of written communication in its potential for permanency, replicability, and transcendence from spatial and temporal constraints. Furthermore, mediated publics enable the persistence of messages in ways that may skew the original context and intended meanings. In this way, online communication complicates traditionally understood boundaries between the oral and the written, the public and the private. This confusion is further exacerbated by a factor that is unique to the Internet: “searchability.” Because most of the information available on the Internet is archived by search engines such as Google, it has become increasingly important to manage one’s online reputation. The process of image management entails not only the calculated projection of symbolic markers of identity, but also an imagining of the audiences that may view this display. Online audiences are not limited to intended addressees and may include family members, employers, educators, corporations, and government agencies. There are many ways in which members of online social networks manage their various unintended audiences. As noted above, some people choose to make their online Profiles private, and thus viewable solely to their immediate networks of chosen Friends. On Facebook, one can also create a “Limited Profile” that displays only certain chosen parts of the Profile, and mark this option when accepting a Friend Request from, for instance, a younger sibling. Within Tribe, it is common to identify oneself by a nickname or pseudonym, which substantially diminishes one’s “searchability.” Eliminating or falsifying identifying factors (such as name, age, and location), another way of reducing one’s “searchability,” is particularly common among teenagers on MySpace (boyd 2007: 4). Despite the growing concerns over unintended audiences, however, many users maintain a comfortable indifference over who might come across, let alone care about, a single online Profile amidst the millions in existence. “There’s nothing on there that’s really inappropriate or troublesome,” Tory says, “So what do I have to worry about?” Many believe that they retain some degree of anonymity, particularly high school students on MySpace. Because of their network nature, interaction and visibility on these sites is primarily between designated Friends in particular niches. When these niches are popularized, they are perceived to be less safe and less exclusive, diminishing trust and encouraging self-censorship; the social context becomes a confusing mix of multiple contexts. Though membership on Facebook was initially limited to college students, in 2005 the site announced its decision to open membership to high school students as well. In response, thousands of college students united to protest the decision. Hundreds of Facebook groups were created, encouraging users to express their concerns to the Facebook administration or to delete their accounts altogether. Many of those who protest Facebook’s “open doors” policy express their fear that Facebook is “turning into MySpace.” Facebook responded quickly by implementing a wide array of privacy features, allowing members to create Limited Profiles and to choose the degrees of separation by which their Profiles may be viewed, such as “friends,” “friends of friends,” or a single network (i.e.; one’s university or city of residence). Despite continued protests over the site’s expansion, however, Facebook eventually opened up still further- starting with corporate networks and eventually opening membership to anyone with an e-mail address. Many veteran Facebook users have expressed nostalgia for the way things were “before Facebook turned evil”- that is, before they betrayed their niche users by opening the site to anyone. Facebook is often cited as a useful tool for finding out the sexual orientation of a potential romantic partner, however, the decision whether or not to articulate one’s sexual preferences can be difficult. Ralph, a Wesleyan senior who recently “came out” to his friends as homosexual, decided not to specify his sexuality on Facebook. His decision was not an easy one:

Ralph went on to describe the stigma of pedophilia that motivates his self-censorship. Gay men working with young boys are often faced with the problem of reconciling the consequences of this stigma with the desire to pass on the all-too-important lessons of tolerance and acceptance. Semi-public arenas such as Facebook and MySpace encourage normativity; notably, these sites both request that members designate their gender as either male or female, and the options for articulating one’s sexuality are also rather binary-enforcing. On Facebook, members can choose to be “Interested In” men, women, or both men and women; on MySpace, members may describe themselves as bisexual, gay/lesbian, straight, “not sure,” or “no answer.” Tribe is a very different story. Displays of sex and gender on Tribe are notably “alternative.” A quick search of Tribes using the query “women” is rather revealing, with the top ten results being: a belly dance gathering for “warrior women,” an article entitled “PA Fines Midwife,” a Tribe called “BDSM [28] Women Only,” another for BDSM women’s parties in San Francisco, another called “Women of Star Trek,” “San Francisco Women’s Film Festival,” “Younger Women for Older Men,” “Empowering Women in Peace Love and Light,” “Bio Boys 4 FTMs [29],” “Understanding Women and Islam.” The focus here is on various modes of empowering women and embracing alternative and diverse lifestyles. A search for “men” yielded the following results: a Tribe called “Men Flirt with Men,” another called “Men of Middle Eastern Dance,” “Gay Men with Depression,” a gay man’s Profile whose handle is “ManDater,” again the Tribe “Younger Women for Older Men,” but this time followed by “Younger Men for Older Women,” a curious Tribe entitled “San Francisco Men’s Auxiliary of SCUM [30] ” (which has a mere seven members), “nature boys: queer men outdoor sports,” “Gay Masculine Men,” and lastly a “SF Citadel Men’s Group” representative of a queer BDSM and kink “community dungeon play space” in San Francisco. While these results are a mere fragment of the community as a whole, the gay male community is certainly well supported on the site. Tribe is a site where the marginalized become the mainstream, helping to positively reinforce one’s “alternative” lifestyle or worldview by creating a safe space in which to express it through Profiles, meet others who share it, discuss it in message boards, and find out about related offline events, gatherings, and workshops. Of the three sites, Tribe is the only one that imposes age regulations on its members. Those under 18 years of age are technically not allowed to join, although it is a simple enough matter to lie when filling out the registration form. Such a regulation is deemed necessary due to the notable lack of censorship on the site. It is not uncommon to come across erotic photograph collections or proud nudists like Jim, whose Profile picture features him seated naked in a camping chair, surrounded by leaves. His About Me section reads: “I am a truck driver & a nudist. I Like Nude Hiking, nude camping, and Skinnydipping.” Such postings are typical of a site primarily focused around “alternative” lifestyles, whose advocates are quite vocal in opposition to censorship and constitute a niche community based on shared values of acceptance and freedom of expression. Tribe is regarded as a safe space for discussions based on shared subcultural interests, such as craft-making or African drumming, but in this way also allows the proliferation of information about subjects that parents may not want their children coming across, such as psychedelic drugs and polyamorous relationships. Precisely this quality of the Internet- its blurring of the public and private spheres, granting young people access to “inappropriate” or “adult” content- encourages a moral panic just as television did half a century ago. Like television, video games, and popular music, the Internet is a medium through which young people learn things about the world that their elders might prefer them not to be exposed to. Unlike television, moreover, the Internet allows individuals to interact with one another in unmoderated environments. This fear is mirrored and magnified in popular media, which circulate horrific cases of naïve children lured out of their homes by sexual predators with such headlines as “MySpace, Facebook Attract Online Predators (Williams 2006)” and “MySpace: Your Kids’ Danger? Popular Social Networking Site Can Be Grounds For Sexual Predators (CBS Broadcasting, 2006)” [31]. Further substantiating the fears of concerned parents and educators, an amendment to the Communications Act of 1934 was passed by Congress, called the Deleting Online Predators Act of 2006. The Act, directed specifically at online social networks and chat rooms, requires schools and libraries to take protective measures on behalf of minors. In reality, such cases are few in number, and usually involve willing teenagers meeting up with adults they have met online. In a recent conference entitled “Just The Facts About Online Youth Victimization,” a panel of four experts emphasized that the revelation of personal information is not what endangers online youth. Rather, most instances of these crimes involve mutual seduction and youthful curiosity and rebellion:

Despite its negative consequences, sensationalized media attention has also contributed to the increasing awareness among online youth of the potential dangers of the Internet. It is common practice to refuse the Friend Requests of unsavory-seeming strangers (as evidenced by their “sleazy” Profile pictures and aggressive, sexualized style of writing) and simply delete inappropriate messages. Rather than being naïve “victims” of “online predators,” those engaged with online social networks typically demonstrate a savvy understanding of communicative norms on these sites. Most are wary of strangers requesting their Friendship, aware of the information they provide about themselves, and strive to establish trusting relationships on the basis of authentic online personas. Nevertheless, the very nature of the Internet allows for inauthentic performances that have much more subtle consequences. There are numerous factors at work that result in the diminishing of trust in and perceived authenticity of others online. Offline, one’s interactions in the public sphere are informed by visible bodily presence, a factor that is profoundly absent online. Because of this lack of visual cues, it is entirely possible that an online persona could be completely falsified. Grace told a story of how her high school debate coach was impersonated by another student on Facebook, with nearly disastrous results:

On MySpace, Profiles of famous people that are created by fans are quite common, though they usually state that they are not the actual person. Nevertheless, other fans will Friend this pseudo-persona and leave Comments as though they were speaking directly to the object of their admiration. Rather than a personal attack, such activities are imaginative and playful in nature. Occasionally, however, fans will express anger when realizing that they have not, in fact, stumbled upon the Profile of their hero. Impersonation is rare on Tribe, though imagined identities are likely to be creative constructions of self, particularly “technoshamans” who seek to provide wisdom and insight for others. One such Tribe member, who Friended me long ago and whose enormously high Friend count (13,179) piqued my curiosity, responded almost immediately to my message asking how and why he has so many Friends:

When browsing through the Profiles of other members on Tribe, I often find that I am connected to them through “Love Is Everything.” Frank’s emphasis that “the message is what is vital, not the messenger” was also expressed by Demetri, who told me, “I’m just a vehicle.” Individuals who acquire a wide audience on these sites often feel a responsibility to project a positive message, minimizing the gritty details of their personal lives and focusing instead on a message worthy of sharing with others, thereby gathering them around a common theme. Though Demetri has thousands of Friends on his primary MySpace Profile, he also maintains a secondary account just for staying in touch with those he knows or wants to get to know, around 180 Friends. On an existential level, some people express anxiety over the authenticity of their own Profiles. “I refashioned my Facebook profile completely this semester,” Lauren recalls, “I was sick of viewing this ‘bubbly’ personality that I no longer felt to be accurate.” These sites allow members to reflect changes in their identities as they occur. While some may strive to portray themselves as honestly as possible through their online Profiles, others see their online identities as co-constructions, informed by who they perceive their audience to be. It is common for people to describe their online personas more as “who I want to be, or how I want to be seen, and less actually who I am (Jackie, 2006).” Others express the belief that not only is honesty impossible, but it hardly matters to them. In one casual conversation, my friend Luke proudly proclaimed, “I care so little that I let her [points to his girlfriend] go in and change my whole profile around. It's ridiculous, and I haven't even changed it back." His statement reflects a common stance in the face of the widespread popularity of Facebook and MySpace. The notion that “I don’t care” is exhibited through a variety of ways, from playful and humorous falsification of one’s Profile to near-total austerity. I’ve increasingly come across Profiles that offer little to no information about the person’s personality, a “functional” Profile that seemingly exists just for the sake of demarcating one’s belonging in a university network. For many users, a preference for face-to-face communication is a principal motivation for minimizing one’s online persona. “I think it becomes easy for people to learn about others in a way that promotes no dialogue or discourse,” Jordan says. Indeed, quick judgments based on subjective interpretations of online Profiles are often cited as one of the most pervasive negative repercussions of the medium. “I’m addicted to stalking people on Facebook,” Danya says, “and judging people based on their profiles.” An individual represents herself on the Internet through modes quite different from face-to-face encounters. When I come across a MySpace Profile, I see the image this person has chosen to reveal, a factor that calls to mind an amateur video popularized in 2005 entitled myspace: the movie, a satirical portrait of MySpace members and the social dramas of the Internet. In one clip, a young woman is said to have “the angles”- all of her MySpace photos are close-up shots of her face, at various unnatural angles so as to accentuate the good whilst concealing the ugly. To my amusement, an old high school acquaintance who recently Friended me on Facebook engages in precisely this activity. Her Profile picture changes multiple times a week, each time an angled face shot that bears little resemblance to the girl I knew in high school. My instinctive judgment is that this girl is extremely self-conscious, vain, and fake. This exemplifies but one of the ways in which the authenticity of an individual’s online persona is questioned. In addition to adding new features to the world of social interaction, social networking sites are also redefining the meaning of a “friend” and how people go about pursuing “friends” and romantic interests. It may be unfair to say that these sites trivialize the concept of friendship (though such criticism makes sense when one sees Friend counts in the hundreds), but most people feel that Friendship is defined more loosely than other kinds of friendship. To illustrate this point, Maria told an interesting story:

The nature of online social networking is such that it allows people who haven’t even laid eyes on each other to be virtual “Friends.” On Facebook especially, it is likely that one will eventually find herself face-to-face with said Friend, resulting in the awkward situation of knowing far more about someone than is comfortable admitting. Many people have described experiences in which Facebook instigated social awkwardness, particularly when bringing Facebook into the realm of the “real.” As Isabelle put it, “You never want to be the one to say ‘hey, I met you on Facebook!’” The Shame! From Surveillance to Snooping to Stalking

As the conversation above attests, there is a sense that surveillance of self and others via online social networks is an intensely private practice, bordering on narcissism. Just as seeming too concerned with one’s popularity was simultaneously “uncool” and common practice, publicly acknowledging the attraction of Facebook is generally considered to be “uncool,” however, it nevertheless continues to be a factor in the daily lives of the vast majority of college students:

The rising popularity of online social networking has been accompanied by the incorporation of “stalking” as a normal, everyday linguistic term. What was once a word reserved for obsessive sexual predators has come to refer to ubiquitous, mundane practices of learning about others through information available on the Internet. However, the line between simple surveillance and outright “stalking” is blurry at best, and ultimately subjectively defined. What may constitute normal “friending” behavior on Tribe, for instance, would be regarded as aberrant behavior on Facebook. These norms are largely informed by the communities the sites seek to represent. Thus, Friendship on Tribe is generally motivated by shared interests marked by membership in particular Tribes, while Friendship on Facebook is typically motivated by shared institutional affiliations (for the most part, schools). On MySpace, however, it is common practice to be “friended” by utter strangers, many of them musicians looking to promote their music, as well as spam robots. When Demetri became a member of Facebook, he “friended” a good friend of mine who had met him only once, years ago, and proceeded to leave a message on her Wall inviting her to an upcoming party. She described the experience as “weird,” noting the plethora of self-taken photographs on his Profile that were littered with “his own comments. I mean, seriously! That’s so narcissistic!” “That’s so MySpace!” I chuckled in response. References to “stalking” are most frequently brought up in conversations centered on matters of the heart. It is common practice to “stalk” a romantic interest online as a safe way of finding out the person’s relationship status, sexual orientation, and social habits. With the rising ubiquity of digital cameras and public online photo albums, a picture truly is worth a thousand words. The following discussion on a Wesleyan message board exemplifies the significance of the visual:

Jealousy would seem to be a principle motivation for “stalking” behavior. One friend confided that she’d spent the previous evening examining the several hundred Facebook photos of her boyfriend’s ex-girlfriend, eventually admitting “she’s pretty cute, I guess.” I commiserated with her, having done the same thing myself in the past. It would seem we’re not alone in this particular guilty indulgence:

The Seductive Power of the Internet For some, the Internet can become a guilty indulgence that allows one to avoid dealing with various aspects of “real life.” Online social networks, in particular, are popularly utilized as tools for procrastination. From personal experience, it is simply too easy (not to mention enjoyable) for me to click away from my word processor and instead indulge in gossip through instant messaging programs and online social networks. It is a distinctly private practice that is frequently looked down upon in public discourse; like most outward expressions of preoccupation with popularity, it is considered “uncool” to be overly concerned about one’s identity on these sites, even though it is rather common in practice. While it is not uncommon for students to sheepishly admit to cruising Facebook when they were supposed to be writing papers, the practice may also be symptomatic of deeper emotional issues. As one blogger confessed, “my days are spent refreshing Facebook a hundred times an hour and sleeping and not dealing with life.” Psychological depression is highly correlated with the breakdown of kin support networks, a phenomenon especially familiar to college students who must create new social bonds upon being abruptly disconnected from their home communities. One person’s advice for problematic Facebook use was to “stop using Facebook for awhile. Have a friend change the password and promise not to give it to you for a month or whatever.” This proposed solution is also advocated by a Facebook Group called “I found a solution to facebook addiction”:

Internet Addiction has recently become a popular topic, evidenced by a steady increase in support groups and psychological research (Leung 2004; Widdyanto & Griffiths 2006; Caplan 2007). Though it has yet to be officially classified as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), proponents of its inclusion have developed a set of diagnostic criteria. These criteria include excessive use, signs of withdrawal syndrome such as anxiety and obsessive thinking, a desire to cut down on Internet activities, reduced involvement in important family, social, occupational, or recreational activities, and a negative impact on one or more of these spheres (Goldberg 2002). These factors are frequently invoked by heavy users of online social networks when describing their personal concerns and anxieties regarding their motivations for such use. Carla, a Facebook “quitter,” recalls:

Carla’s confession is not unusual. Rather, it reveals the obsessive thought patterns and social anxiety some experience in tandem with heavy involvement in online social networks. These sites encourage quantitative comparisons of one’s social capital with that of others. For this very same reason, I am able to quantitatively demonstrate the prevalence of those who label themselves addicted by joining Groups of fellow addicts. A search for “Facebook addict” displayed 230 Facebook Groups pertaining to the topic, ranging from Alcoholics Anonymous-style support groups to proud and seemingly casual declarations of one’s identity as a “Facebook Addict.” A similar search for “MySpace Addict” on MySpace yielded 67 public Groups; however, it is impossible to tell how many private Groups for MySpace addiction are in existence. Less-populated Tribe is not without its own Group of “Tribe Addicts,” currently with 171 members. As is the case with most addictions, overuse of online social networks is often accompanied by feelings of shame and guilt. Rather than merely observing and fantasizing about the life one wishes to lead, however, some conceptualize their “addictions” in a positive light, demonstrating enthusiasm for the socially beneficial aspects of the medium. Nevertheless, it is also common practice to tease those who spend a good deal of time on these sites:

Carla’s testimony reflects pride at having overcome what she saw as a debilitating habit. However, shortly after our interview she rejoined Facebook and resumed normal Facebook activities- creating Events, posting messages on her Friends’ Walls, and uploading photographs. Facebook makes re-joining a very easy process, allowing those who have deactivated their accounts to rejoin at any time simply by re-entering their e-mail address and password on the site. Furthermore, the site archives all user information such that upon re-joining, it is as if one never really left. As the popularity of online social networking grows, a host of privacy issues are brought to the fore. They are dealt with in various ways, ranging from apathetic dismissal of one’s visibility, to privatization or simply elimination of personal information on Profiles, to collective and occasionally effective protest. While users of MySpace and Facebook have increasingly had to respond to the sites’ expanding publicity, however, Tribe remains a relatively restricted niche. Thus, the site enables playful performances and transgressive acts by significantly decreasing the chances that one will “be seen” by those in positions of authority. While the “top-down” gazes of authority figures and advertisers are often configured as problematic, users of these sites also describe concerns with the horizontal gazes of the members themselves. While many of my informants condemned social networking sites for contributing to a perceived decline in face-to-face interaction, by and large these sites serve simply as extensions of preexisting communication practices. The ubiquity of social Internet use among younger generations has given rise to the use of online social networks for expressing friendship bonds and group affiliations, lending an explicit affirmation of belonging in the world. In one of my interviews, a student related to me that before she came to college, her older sister informed her that “you don’t exist if you’re not on Facebook.” It is precisely this mentality that may lead some to depend on these visual articulations of their social worlds, especially in times of loneliness and depression. Online social networks enable the virtual expression of longstanding offline obsessions with effectively performing one’s identity, demonstrating one’s popularity, and acquiring information about romantic interests. Being overly concerned with the “authenticity” of one’s social identity is common among young people struggling to find their place in the world. However, online social networks enable new forms of creative self-expressions by allowing individuals to portray themselves as they see themselves through multimedia, constructions effectively broadcast to one’s social network. While online social networks certainly may reinforce the importance of popularity, a traditional student concern, those overly obsessed with acquiring “Friends” are kept in check by the risk of being labeled a “MySpace Whore” or a “Friend Slut.” Self-admitted “addicts” can easily find support within the medium, and “stalking” others online has come to be a casual colloquial term- demonstrating the pervasiveness of the act in everyday life. Dystopian views based in the potential dangers of the medium are not to be dismissed, however. Online privacy has become a widespread topic of controversy, prompting legal actions (such as the Deleting Online Predators Act of 2006), academic research studies, and a variety of organizations dedicated to disseminating information for protecting Internet users (such as the Internet Safety Technical Task Force, headed by Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society). The reality of these online practices is that much, if not all, of the personal information members provide can very well be used against them by legal authorities and exploited by commercial interests, and is definitely stored in centralized databases. The complex and sometimes problematic issues and anxieties discussed in this chapter only partially portray the “virtual campfire,” which combines the traditional “campfire” activities of gossip, interactivity, and group belonging with the “virtual” elements of permanency and public exposure. In the next chapter, I seek to balance these perspectives by examining the pleasures and utopian ideals described by members of these sites. >> Chapter Five: Pleasures and Utopias NOTES

|

© Jenny Ryan 2008 |